The First Scientific Concept of Rockets for Space Travel by Robert Godwin Part 11

From The Space Library

Contents |

Conclusions

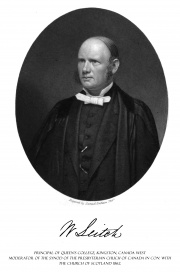

Leitch’s book would see its third edition, first in New York in 1866, and the following year in England. The fourth edition appeared in 1875. It was still in print until at least 1877 and as has been previously noted, it would then be plundered and anthologised for at least another three decades beyond that; evidently without attribution.

This book would be his one great work in a short life of only 49 years. The new chapters he added to the book in 1862 included his efforts to address the age and nature of the universe and the possibility of alien life; both subjects guaranteed to rock the halls of the literalist interpreters of Christian scripture.

The Eternity of Matter

His essay The Eternity of Matter was an attempt to unravel the metaphysics and conflicting philosophies in vogue at that time. After a short assault on those foolish enough to try and create definitions for infinity, Leitch in his usual way touched on the heart of the matter. His peers were battling over the evidence for intelligent design in the universe, a battle which in some quarters continues to this day. After some had argued that the non-eternity of matter was a purely scriptural truth, beyond the reach of human reason, Leitch postulated an insight that, despite being grounded in his belief in a Creator, could almost be taken as a description of the Big Bang, “If we admit the argument of design…may we not legitimately push the argument somewhat further, and hold that matter itself must have had a beginning? For example, the solar system manifests design, and had, therefore, a beginning; but the matter out of which the system was formed must have been wisely adapted for such a cosmical combination; and are we not entitled to infer that this chaotic matter had a beginning also, or that matter is not eternal?”

Again we can see him ploughing headlong into the biggest question of all; a question still evading a clear answer 150 years later.

The Plurality of Worlds

Finally, when addressing the notion of alien intelligence Leitch once again challenged his religious peers by shredding all of their assumptions; generally those derived from scripture. Despite believing in a Christian universe Leitch was not willing to fall into the trap of assuming that a version of the Christian Saviour was dropping in on every planet on a mercy mission. Nor was he willing to accept that the universe was made solely for humans. He proposed that it might just as easily be possible that only the Earth and mankind had committed mortal sins and that we might well be the black sheep of the galactic community. [1] He argued in favour of alien intelligences in a multitude of forms because the Bible not only didn’t preclude them, it described them - as Angels. In his final analysis Leitch used his own faith to rationalise why we seemed to be alone in the Universe. He suggested that perhaps only mankind had fallen into God’s bad books and we were consequently ostracized by the other galactic intelligences until we had redeemed ourselves. It was a poetic and typically logical explanation from a man restricted on two fronts, by faith and science.

A Night in an Observatory

In his 1862 essay “A Night in an Observatory”, he reminisced about the long cold nights spent watching the sky at Nichol’s Glasgow observatory and almost lamented the loss of his naivety regarding the Cosmos. “What should be the most marked moral feature of the astronomer’s character? One would think that, as it is the business of their lives to look up to this inverted hand of God, they would be habitually impressed with His glorious presence… (but) the sailor on the masthead of a ship-of-war was in a better position for forming a right judgment of the battle-field and the glory of the victory, than the man who was in the thick of the fight.”

Legacy

Long after Leitch’s death, John Nichol, the son of Leitch’s astronomy teacher, recalled, “Mr. Leitch, had distinguished himself by the display of unusual mathematical talent, and attracted my father’s attention in the astronomy class. He did all his work with an admirable perseverance, and a degree of slowness almost exasperating. Some indolent people alternate idleness with an amount of activity at times; others, like large bumble bees, never idle, nor ever active, drone through a good day’s work every twenty-four hours. Of this latter order Leitch was. I see him like a shadow in the past, jotting down with slumberous accuracy the records of the hygrometer, no morning was wet enough to damp his ardour; or noting the transit of the stars, no night was cold enough to make him shiver; I hear him, as we are discussing metaphysics together over the fireside of Monimail… I fancy him delivering his address as Principal of King’s College, Toronto, (sic) and the images are of the same substantial, excellent man of this world and the next.” [2]

So what can be deduced from the life of this quiet Scottish-Canadian minister? The context provided in the first few pages of this paper serves to demonstrate how Leitch was chronologically far ahead of Tsiolkovsky and Goddard, but it still doesn’t persuasively position him in a place and time. The fact that Charles Dickens had just written Great Expectations may have some resonance for the reader; or that the first shipment of oil was dispatched that year from America to Europe; or perhaps more salient to the discussion would be a quick survey of the state of the art of rocketry.

When Leitch wrote of his space rocket the British engineer William Hale had only just received his patent for his rotating artillery rocket. The earliest metal rockets, powered by black powder and steered by a stick, had appeared in battle during the Napoleonic wars. They were wild and unruly and as dangerous to the man launching them as to his enemies. Hale’s primitive lump of metal and gun powder, about a foot long, was the best kind of rocket available when Leitch proposed riding a rocket into space.[3]

It is perhaps also worth noticing that after Leitch returned to Canada for the last time, his publisher in Scotland felt that it was advisable to continue the monthly astronomy essays. Leitch was replaced by no lesser light than Sir John Herschel, three time president of the Royal Astronomical Society. Herschel began the task of succeeding Leitch by writing a series on comets.

A review of Leitch's book appeared in The Reader which said, "We cannot conclude our notice of Dr Leitch's book without dwelling upon the admirable manner in which the astronomical facts contained in it are blended with practical observations and the highest and most ennobling sentiments. It is thus that books on popular science should ever be written."

In his home parish of Monimail in Scotland Leitch’s name is inscribed on the monument where his wife and two sons were laid to rest. In his adopted country of Canada the loss of William Leitch was felt so keenly that his colleagues at Queen’s College resolved to erect a monument to him. They wrote to his friends in Scotland who agreed to send £100 if Canada would chip in £200. [4] This led to the establishment of a college plot at the Cataraqui cemetery in Kingston where Leitch was laid to rest on October 4th 1864, exactly ninety-three years to the day before Sputnik.[5] The inscription on the obelisk makes note of the fact that two scholarships were set up in his name by his friends in Canada and Scotland, “to commemorate Dr. Leitch’s learning, educational ability and Christian worth.” [6]

Tsiolkovsky, Goddard and Oberth all became school teachers. All three taught science and all three were inspired by the fantasy of science fiction and the practicality of science fact. Leitch was also a science teacher. In a world essentially bereft of science fiction his inspiration seems to have been his religion, along with the exciting new technologies of the industrial revolution, and the intractable laws of Isaac Newton.

Ironically, of this illustrious group Leitch was the only one who was truly contemporaneous with Jules Verne and on at least one occasion the two were within a few miles of each other. Verne's mother traced her heritage back to Scotland in the 15th century. Jules Verne visited both Fife and Glasgow when Leitch was regularly traveling back and forth between the two and still living in Monimail in the summer of 1859. Verne's visit happened just a few weeks after Morris had arrived from Canada to talk Leitch into taking his post in Ontario. Verne crossed the Firth of Forth in a bad storm and had to be rowed ashore "sick and wet" before taking shelter at Inzievar House (which Verne called Oakley Castle), just thirty miles from Monimail. The owner of the house, one Archibald Smith-Sligo owner of the enormous Forth Iron Works, had at that very moment gone off to Edinburgh to take part in a national mobilization of volunteers to create artillery and rifle divisions. In early 1860 he became Captain of the Edinburgh Volunteer Rifle Corps and had periodic drills and inspections at Oakley. This important mobilization movement may, in part, explain the timeliness of Leitch's lectures on rifles. Verne was invited to Oakley by the brother of the owner of Inzievar, the Reverend William Smith, an up and coming Catholic priest who would later become Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh.

Perhaps less surprising is the fact that both Verne and Leitch shared a common fascination with Brunel's enormous Great Eastern super steamship. Verne would experience another hair raising passage, this time aboard the massive paddle steamer, and ended up in Niagara Falls Ontario, in 1867 just at the time he was half way between the publication of his two famous space adventures; but of course Leitch had expired three years earlier.

Twenty seven years after Leitch’s death Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, was laid to rest a few hundred feet away in the same cemetery. Today it is a National Historic Site. Despite never sharing in the King’s endowment Queen’s became a prestigious University and one of its most famous alumni would be Elon Musk, owner and founder of SpaceX.

Leitch’s death would even make the newspapers 100 years later. On that day Jack McKay, an American with a Scottish background, rode a rocket-propelled X-15 aircraft to the edge of space.[7]

A fitting place to conclude the story of Principal William Leitch would seem to be an extract from Invocation To Professor Boss, Who Fell Into The Crater Of Mount Hecla by Norman Macleod.

- Oceans of endless bliss Shall roll within thy kingdom;

- Cataracts of matchless eloquence shall hymn thy praise;

- Mountains of mighty song—mightier by far

- Than Hecla, where thine ashes lie entombed,

- Shall lift their heads beyond the top of space,

- And prove thy deathless monuments of fame;

- While thou with kingly, bland, benignant smile,

- Look’st down upon the earth’s terraqueous ball,

- And quell’st with thunder Neptune’s blustering mood.

THE END

Further reading

The Globe Toronto Jul 11 1844, Oct 8 1844 , Sep 29 1847, Dec 29 1847, Apr 14 1849, Dec 13 1859, May 7 1860, Nov 10 1860, Jan 20 1862 , Apr 30 1862, May 29 1862 , Jun 7 1862, Jun 26 1862, Dec 6 1862, Mar 6 1863, May 14 1863, Nov 18 1863, Feb 13 1864, May 12 1864, May 14 1864

Queen’s University, Roger Graham and Frederick Gibson, McGill Queens University Press, 1978

Queen’s University at Kingston; the first century of a Scottish-Canadian foundation, 1841-1941. Delano Dexter Calvin, The Trustees of the University, 1941

A disciplined intelligence: critical inquiry and Canadian thought in the Victorian era, A.B. McKillop, McGill Queens University Press, 2001

Daldy-Isbister Catalog, 1876

The Extra-terrestrial Life Debate by Michael Crow, Cambridge University Press, 1986

The Missionary’s Warrant by William Leitch,The Church of Scotland Pulpit, Macphail, Edinburgh, 1845 The American Golfer, Volume 16. Story on Cecilia Leitch

Astronomy a Century Ago by A.V. Douglas, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 58, 1964

Acknowledgments:

With thanks to the staff at the University of Guelph Library Annex, McMaster University Archives, Knox College and Trinity College Toronto, Mr. Frank Winter, Mr. Hugh Laidlaw at Monimail, Ms. Julie Greenhill at St Andrews University, Mr. Hugh Chambers, Mrs. Patricia Godwin, Mr. Hugh Black, Mr. Chuck Black, Mr. John Pearson at the Women’s Golfing Museum, Ms. Jessica Hood at Cataraqui Cemetery, and Ms Deirdre Bryden at Queen's University Archives.

About the Author:

Robert Godwin is the author and editor of dozens of books on spaceflight. He is a member of the International Astronautical Federation History Committee and was Space Curator at the Canadian Air & Space Museum in Toronto. His imprint Apogee Books was winner of the “Best Presentation of Space” award from the Space Frontier Foundation. The Minor Planet Godwin 4252 is named after him for his contributions to space history. He lives in Burlington Ontario.

Footnotes

- ^ This notion was stretched even further by the noted Christian scholar and writer C.S. Lewis, who in his 1958 essay God in Space argued,"There might be different sorts and different degrees of fallenness." Lewis famously debated Arthur C. Clarke to a stalemate on these issues between 1943 and 1954. Clarke was still willing to let Lewis voice his opinion, four years after his death. He included Lewis' God in Space in his 1967 anthology The Coming of the Space Age". Clearly Leitch would not be the first, or the last, to struggle to reconcile the Plurality of Worlds with his faith.

- ^ Memoir of John Nichol, James Maclehose And Sons, Glasgow, 1896

- ^ Chamber’s Journal, Volume 3, Jan-Jun, 1855

- ^ Documentary History of Education in Upper Canada by J. George Hodgins, Vol 18, Cameron, Toronto, 1907

- ^ Cataraqui Cemetery Archives, Kingston Ontario

- ^ Documentary History of Education in Upper Canada, Warwick and Rutter, 1907

- ^ Quebec Chronicle Telegraph May 12 1964